“We have art so that we shall not die of reality.” — Friedrich Nietzsche

The book of Genesis in the Bible famously says that God created humanity “in our own image.” We’ve returned the favor – creating Gods in OUR own image. That is, human-like, only really really big. For example, the God of the Bible may not have a physical body, but certainly behaves in all too human ways: He loves and hates: “Jacob I have loved, but Esau I have hated.” (Mal. 1:2-3). He exacts revenge: “Vengeance is mine, says the Lord, I will repay.” (Deut. 32:35). He regrets: “The Lord regretted that he had made human beings on the earth.” (Gen. 6:6). He is jealous: “Do not worship any other god, for the Lord, whose name is Jealous, is a jealous God.” (Ex. 34:14). Examples abound.

It’s called “anthropomorphism” – “anthropos” = human beings and ‘morphos’ = the form of something. So anthropomorphism is projecting human traits and actions onto things and situations that aren’t human, such as pets, or “an angry storm,” or “my phone died.”

Personally, I’m thinking that any Creator would have concerns greater than our all too frequently ignoble human emotions about tiny human affairs. (As we float on a speck of dust circling an unremarkable star in a forgotten corner of one galaxy among the 150 billion or so in the observable universe alone.) Ants may as well discuss how Einstein must have antennae and six legs.

The Greek philosopher Protagoras (5th century BCE) famously said: “Humanity is the measure of all things.” Hardly. For example, a six-foot tape measure may be an appropriate tool for measuring the height of humans and human things. But it’s not so good for measuring the size of a virus, or the size of the sun.

My point is that of course we humans experience everything from the fish bowl of our human consciousness. But it’s still a fish bowl – in the vast ocean of the Cosmos.

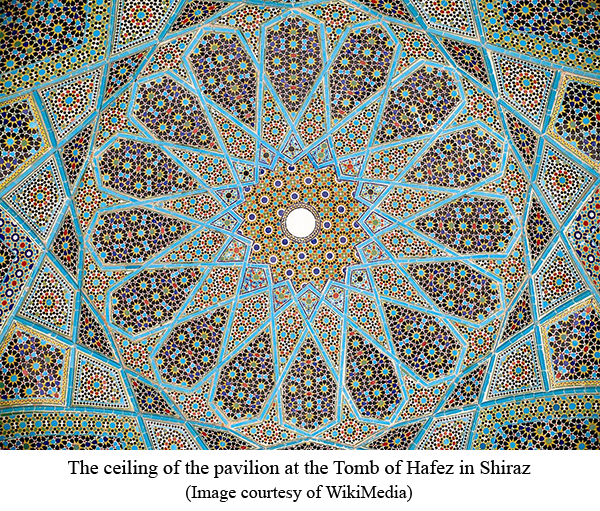

Islam has a rather unique approach to anthropomorphic depictions of Allah — they simply forbid them! Instead, when decorating their mosques, they use geometric designs. Since they’re not representational, they completely side-step any possibility of anthropomorphism. And geometric patterns align with the Islamic view of Allah’s transcendence, infinity, orderliness, and perfection.

And they’re gorgeous!

And we find plenty of examples of ‘sacred geometry’ (geometry in service of the sacred, the sublime) outside of Islam. The design and proportions of the Egyptian Pyramids are believed to embody sacred geometrical principles. Greek architecture, including the Parthenon, incorporates the ‘golden ratio’ (a mathe-magical number like Pi). Gothic Cathedrals often feature intricate geometric designs such as rose windows (rose windows being relatively rare in secular contexts). And Hinduism and Buddhism have their mandalas.

So I’ve wondered how “sacred geometry” might be applied to music.

“Objective Art”

Objective art refers to the concept that Art is based on universal principles and objective criteria rather than personal, subjective experiences or tastes. That certain elements — such as harmony, proportion, and symmetry — can evoke specific, predictable responses in viewers due to fundamental principles of order and beauty inherent in nature and human perception. In short, the idea that music in particular really is a “universal language.”

I personally don’t buy it. For one thing, when I listen to music from different cultures — Indian ragas or Indonesian Gamelan — on a very superficial level I can appreciate its immediate sheen of beauty. But I know I’m not grasping 99% of what’s going on. In the same way that if someone from India or Indonesia is speaking to me, I can grasp their general emotional state from their tone of voice (happy? angry?), but beyond that, I haven’t a clue what they’re saying. Heck, even to a Westerner, a fugue by Bach makes little sense without prior explanation!

But I do think there is something to the idea after all. Namely: what is the focus of a piece of music? Is it focused on portraying the feelings of the composer? Nothing wrong with that! We all live in our private fish bowls of consciousness, and why not express that musically? It’s all part of human experience and Art. But what if one wanted to describe the Transcendent, the Sacred, the Sublime musically? (Music might have better luck than language!) Of course, the best I can probably hope for is to express “my” feelings about the Sacred, not the Sacred itself. Still, it’s a shift in focus. Instead of being entirely anthropocentric — ME-centric, it’s at least trying to tackle something greater than myself. So instead of trying to express and invoke feelings of joy or sadness (as valid as that is), perhaps one could try to invoke feelings of the sublime. Or maybe even effect a shift of consciousness – something trance-like.

This is hardly a new idea. Indeed, before the Enlightenment (roughly 1750), music had a role in society very different than today. Before 1750, sacred Western music was considered a medium to glorify God, elevate the soul, and reflect the divine order of the universe through structured forms and mathematical harmonies. Composers like Palestrina and Bach created works that adhered to strict compositional rules aimed at achieving spiritual transcendence and communal worship. (Gregorian Chants, for example.) With the onset of the Enlightenment, the role of music shifted dramatically towards individualism, personal expression, and public entertainment. The emphasis moved from the objective spiritual impact of music to its capacity to convey personal emotions, explore human experiences, and provide aesthetic pleasure.

(Note: J.S. Bach died in 1750, making him a convenient marker for the end of a great era in Western music aesthetics, encompassing the Medieval to the Baroque. An age when music was considered to concretely affect people – individually and as a community. As opposed to the Enlightenment when music was demoted to mere entertainment.)

Today some modern composers are trying to skip the Enlightenment aesthetic and pick up where Bach left off. These include Arvo Part, John Tavener, and Henryk Gorecki.

The Sacred vs. the Secular

Even in Medieval times, not all music was sacred. But sacred music was very different from secular: Gregorian Chant (chanting monks and organs) vs. Troubadors (like guitar-playing folk singers). Over the centuries the two styles became more and more similar, until by 1700 or so, the only difference between sacred and secular would be the sung text (if there was sung text).

Today, many churches claim it’s a ‘good thing’ that their music sounds just like what you hear on mass media, only with religious words. But I wonder… in Medieval times, when you went to church, you stepped into a space (a cathedral) unlike any space in your community, and heard music unlike anything you heard anywhere else. Might that heighten the spiritual experience?

Which Brings Me To…

Which brings me to where I’m at. I don’t want to write ‘mass media’ music anymore. I want to write music about the spiritual (not any particular tradition). Music that isn’t about me me me.

And music that applies ‘sacred geometry’ to music. (I have ideas for doing that — stay tuned for future blogs.)

Also, why not use instruments already associated with the sacred as the backbone of my sound? Such as pipe organs, which are awe-inspiring right out of the gate. By the way, the pipe organ was invented in Alexandria, Egypt around 300 BCE — sounding something like a bagpipe, but with a small keyboard. The Romans loved it and used it in their coliseums — much like we use organs at baseball games. The organ didn’t really catch on in the Church until about 1000 CE, meaning the pipe organ was a secular instrument for far longer than a sacred one. (That also makes the pipe organ the oldest keyboard musical instrument, millennia older than the piano.)

I have unconventional ideas on how to use the pipe organ, which I’ll also discuss in future blogs. Furthermore, there are pipe organs outside of the American tradition that sound very different, and I’m using those too.

Other traditionally sacred instruments would include gongs, bells, and harps.

So, here is my first piece trying to apply some of these ideas. It’s a preliminary sketch of what I dimly envision — something that will evolve and become more clear as I write more. I look forward to your feedback!

This article first appeared on SubStack.

Leave a Reply