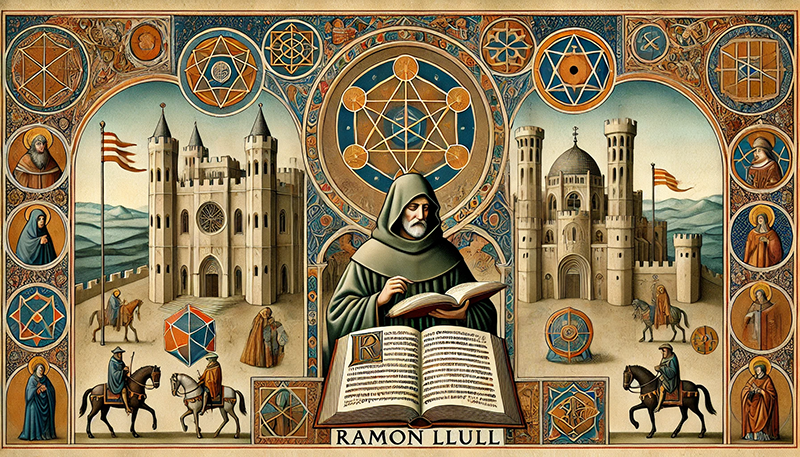

The Book of the Order of Chivalry (c. 1275), was written by Ramon Llull (1232–1315), a polymath and Christian mystic from Majorca. Llull thought that knights should be chosen, trained, and ordained like priests. Llull’s book became a handbook of chivalry throughout much of Europe. Being a Christian mystic, of course he writes about Chivalry using Christian vocabulary. But I think his ideas transcend any particular Spiritual Tradition.

Llull wrote over 250 books on a wide range of subjects, including theology, philosophy, logic, science, and even poetry. (And one on Chivalry!) He is best known for his book Ars Magna — a groundbreaking philosophical and logical system that aimed to uncover universal truths using mathematics — now considered the invention of Mathematical Combinatorics. He was also known for his interest in memory and logical systems more generally: his method of linking virtues to physical objects is an example of the ancient memory technique known as the Memory Palace.

An overview of the Order of Chivalry, and a linked table of contents to all my blogs (with music) on various chapters of Llull’s book can be found HERE.

Here Llull equates the knight’s sword with ‘justice’: (more…)