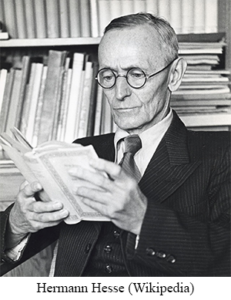

Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) was a 20th-century German author with a stature in that language more or less equivalent to Hemmingway or Melville in English.

His last novel was The Glass Bead Game, for which he was awarded a Nobel Prize in Literature (1946). Most Nobel Prize-winning literature goes over my head, but not this book. Well, maybe it goes over my head, but I really like it anyway! It has been a perennial favorite of mine, having read it several times. (The German title is Das Glasperlenspiel = “The Glass Bead Game.” But it has also been published under the name “Magister Ludi” = “Master of the Game”.)

The Glass Bead Game takes place at an unspecified date centuries in the future. Hesse suggested that he imagined the book’s narrator writing around the start of the 25th century. The setting is a fictional province of central Europe called Castalia, which was set aside for the ‘life of the mind’ — something like a nature preserve for scholars/artists. Technology and economic life are kept to a strict minimum. Castalia is home to an austere order of monk-like intellectuals with a twofold mission: to run boarding schools and to cultivate and play the Glass Bead Game, whose exact nature remains elusive. The rules of the game are only alluded to — they are so sophisticated that they are not easy to imagine. Playing the game well requires years of hard study of music, mathematics, and cultural history. The game is essentially an abstract synthesis of all arts and sciences, consisting of players making deep connections between seemingly unrelated topics.

An example of a ‘game premise’ (made up by me) might be “explore the interconnections between Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, the philosophical ideas of Plato’s Theory of Forms, and the rise of the Papacy in the Middle Ages.” Players are judged by who produces the most artistic and profound analysis. I’m not interested in trying to reproduce the details of Hesse’s Glass Bead game — he deliberately provides almost no information for doing so. But I love the general concept of it.

As children of the Enlightenment, our culture emphasizes Scientific Truth, but also historical truth. And especially utility — “What’s it good for?” We’re really busy developing more Science and then finding uses for it.

But I also think humans can be otters, frolicking in a sheltered cove called “Earth”, off the Endless Dark Ocean of the Cosmos. Cavorting in the ocean of knowledge and ideas, connecting them in interesting ways. Not because it has any practical use, but for the sheer joy of curiosity and making interesting connections — just for the hell heaven of it. To play with the mind, ideas, and the knowledge we’ve accumulated over the millennia. Being an artist whose medium is not (just) paint, or musical notes or clay, but also history, and mathematics, and everything beautiful that humans have created. The Mind — the most extraordinary toy there is!

Curiously, sometimes our more outrageous mind-toys turn out to be useful after all. Recall Euclid’s geometry — the basic geometry we all studied in high school. One of its theorems is that the angles in a triangle add up to 180 degrees. In the 19th century, mathematicians asked themselves: is it possible to construct a valid geometry in which the angles in a triangle always add up to LESS than 180 degrees? Indeed you can: one was discovered/invented by Nikolai Lobachevsky (1792-1856).

So, is it also possible to create a geometry in which the angles in a triangle always add up to MORE than 180 degrees? Indeed you can: one was discovered/invented by Bernhard Riemann (1826-1866). These remained obscure mathematical curiosities, studied by almost no one, until it turned out Riemann’s weird geometry was just the thing that Einstein needed to describe the warping of space-time in General Relativity (published in 1915). Today, Reimann’s weird geometry is required study for physicists.

But we don’t always do these things because someday they might be useful. We engage in all sorts of creative and knowledge-seeking endeavors, just for the joy of them, with no concern that they might ever be useful.

So a perfectly reasonable pastime for a self-respecting otter is to find stones in the cove, and play with them – for the all too brief time which is our lifespan. Leaving an uncountable number of stones untouched. Meanwhile, frolicking in the ocean of ideas and knowledge is more fun than a human being should be allowed to have!

William Zeitler

This article first appeared on SubStack.